In Barrington Stage Company’s stunning new production of Kander and Ebb’s beloved Tony Award-winning musical Cabaret, the audience gets its “willkommen” while filing into the lobby of the Boyd-Quinson Stage in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Atop the snack bar, tiny Tiffany Topol—playing Texas, a member of the Kit Kat Ensemble——sings a suggestive song, strumming a ukulele and serenading the shuffling crowd. Other Kit Kat Klubbers—easily identifiable by their barely-there lingerie-like costumes—mill amongst the matinee ticket holders.

The full Kit Kat Ensemble is already in motion as the audience members find their seats in the smoke-filled theater, strutting through the aisles and chatting up theater-goers, stretching on set, enacting some onstage BDSM pantomimes. Stage lights sweep the space with predominantly purple hues. A few lucky ticket holders are seated at bistro tables on either side of the stage, where ensemble members slinkily interact with them. Finally, the nine-piece Kit Kat Band, taking up a good portion of the stage, strikes up the tune we’ve all been waiting to hear ever since BSC’s new artistic director, Alan Paul, announced he would be directing Cabaret as the main stage opening musical.

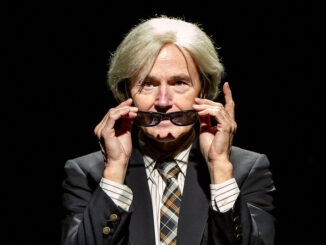

All attention goes to the Emcee as soon as actor Nik Alexander slithers on stage to kick off the show with “Willkommen.” Alexander’s cheek bones are as sharp as cut diamonds, and his quirky, kinky performance—slipping from snakey and sinuous to spasmodic and demonic—is riveting; whenever he’s onstage, you can’t look away. He fully embodies the louche milieu of the Kit Kat Klub, and he lords over the stage with the air of a sly ringmaster of debauchery.

It’s likely that there has never been such a diverse ensemble onstage in the Berkshires; putting the trans in transgressive, this show would likely be shut down by the authorities in those sorry states attempting to ban drag shows, cross dressing, and genderqueer identification. Also, the actors bare a bit of—to quote another iconic musical—tits and ass—but not so much as to be gratuitous, just a few times, as naughty punctuation.

Somehow I made it through adulthood never having seen either a theatrical production of Cabaret, nor the 1972 film by Bob Fosse, although I did come to this show with superficial knowledge of the story and solid familiarity with the score. I’m pretty sure most Berkshire audiences are well acquainted with this iconic musical; indeed, my companion even performed in a high school production—something difficult to imagine these days!

All this to say, I don’t need to go into the plot of such a well-known play. I do assume that Paul’s interpretation of Cabaret represents a pointed reaction to—or even a push-back against—the culture wars taking place across our country and a warning as to what can happen if we choose to disregard the rise of nationalism, populism, and White supremacist rhetoric here and now. Even as I write this, the local paper has reported that National Front posters and banners have cropped up across the liberal bastion of the Berkshires. Message received.

In addition to the magnetic Emcee and the gyrating, gymnastic shenanigans of the Kit Kat Ensemble, many specific elements of this vivid production deserve special mention.

The acting in the story outside of the Kit Kat Klub cuts deep. In particular the romance between Fraulein Schneider (Candy Buckley) and Herr Schultz (Richard Kline) is moving and convincingly conveyed. We feel for them as they first dance together—gingerly, tenderly, hoping for a chance at love late in life. When Ernst Ludwig (Tom Story) sinisterly warns Schneider about tying her fate to a Jew, we know the relationship is doomed, even before she breaks off their engagement; the power of the acting makes these plot developments heart-rending. And later, when we see her with a swastika armband, it’s devastating.

A few more highlights: A pantomimed sequence of the naive American Clifford Bradshaw (played by Dan Amboyer) smuggling material from Paris to Berlin juxtaposed with the performance of “Money.” The giddy performance of “Two Ladies,” with excellent use of a dowstage trap door that turns a trunk into a clown car of Kit Katters. Ludwig’s removal of his jacket, revealing a swastika armband, eliciting a collective gasp from the audience, as well as Cliff’s shock at realization that in his wish to stay ignorant of the contents of his smuggled briefcases, he has been working on the side of evil. Trans and non-binary members of the Kit Kat Ensemble wearing Nazi uniforms and hobnobbing with Ludwig, who looms threateningly when things get a little too wild at the club. The Emcee in a Nazi uniform, looking like his head is about to explode. The prostitute Fraulein Kost’s casual antisemitism; Alysha Umphress delivers a subtle and convincing portrayal of a woman at the bottom of the social ladder who is happy to have found someone she can look down on.

The design elements are outstanding, often creating an over-the-top, sensory-overload experience. Scenic designer Wilson Chin has created a visually stimulating Kit Kat Klub centered on the band. It’s absorbing even without the actors onstage, keeping our eyes busy scanning for details. With very little space at the front of the stage, he conjures the play’s other environments through simple suggestion: trains—a few of those bistro chairs arranged in rows; Clifford Bradshaw’s room at Fraulein Schneider’s boarding house—a door, a desk, and a chaise; backstage at the Kit Kat Club—a clothing rack and a makeup table. Lighting design by Philip Rosenberg stuns the audience on multiple occasions, as when the audience enters into that purple haze; when disco balls swirl, sending delightful sparkles throughout the theater; or when a spotlight’s sudden, harsh, white-hot glare brings us back to the reality of Hitler’s ascendance.

Kudos also to choreographer Katie Spelman, who keeps the Kit Kat Klub denizens moving with carefree abandon in the first act. The pyrotechnic action comes down down to earth as the second act progresses; lofty dancing becomes gravity-bound, leaden. The choreographic transition echoes the dramatic arc. Song and dance superlatively come together in an extraordinary duet between the Emcee and Helga (played by lithesome Kim Hudman), wearing a pig mask, as he sings “If You Could See Her.” The final line—She wouldn’t look Jewish at all—never fails to shock; in this performance, it’s staggering.

Superlative work by costume designer Rodrigo Muñoz amplifies the shifting political environment. In the relatively carefree first act, the Kit Kat Ensemble sports sexy finery—corsets and bustiers, stockings and garters, revealing thongs—the likes of which could be found in a Frederick’s of Hollywood catalog. In the second act, they wear sack-like black dresses that open to reveal swastikas. Sally Bowles takes her first solo, “Don’t Tell Mama,” in a fluffy confection, a buttoned-up white chemise over endless layers of black tulle stopping several inches above her thigh-high leather boots, all the better to flip up her skirt at the audience. By the end, when she sings the musical’s signature song, she’s in a shapeless black tank dress and sensible shoes, more in keeping with a funeral than a cabaret.

As Sally Bowles, Krysta Rodriguez deftly portrays the character’s transition from happy-go-lucky to defeated and empty inside—literally. Rather than the celebratory, uptempo rendition of the title song we know so well, belted out by Liza Minelli, this Sally leaves us with a mournful, heart-breaking “Cabaret,” voice cracking, eyes tearing, stance unsteady. Rodriguez delivers a masterful dramatic journey—finally seeming to recognize the reality of her situation and all that she has lost—and she sings with searing emotional impact.

Another striking moment: Three Kit Katters backstage, strip away their wigs and costumes, affectingly sing “Tomorrow Belongs to Me.” All three—Rosie, Frenchie, and Victor—are played by either trans or non-binary actors: Charles Mayhew Miller, James Rose, and Ryland Marbutt, respectively. Given the tragic history of Europe in the 1930s, the audience knows the folly of this song’s sentiment coming from these individuals, who would soon be labeled sexual deviants and subject to as much persecution as the Jews, Catholics, and others viewed by Hitler as miscreants to be eliminated. Are they blind to what’s going on or so secure in their German nationality that they think no harm could ever come their way?

This brings us back to a quick moment from the Emcee’s rendition of “Willkommen.” As he delivers the lyric,” In here, life is beautiful,” instead of sweeping his arm around the room, the Emcee taps his skull. This small, subtle movement, echoed again toward the end of the show, points to a central conceit of the production. How much can you ignore to maintain your illusion that everything is just fine? Herr Schultz refuses to acknowledge that his life is imperiled. When a brick crashes through his storefront window, he chalks it up to kids being kids. He expresses confidence that these bothersome politics will blow over soon enough, but deep inside, does he know better? Is he pushing those fears aside?

Cliff is subject to a different kind of delusion. When he awakens to the immediacy of the Nazi threat, he makes arrangements to flee Germany and bring Sally to America, where they will live happily ever after with the baby she’s carrying. But it’s an impossible dream, not only because she’s set on staying in Berlin to seek a stardom that will never materialize. He’s also in denial about his homosexuality, which having a wife and a baby would not erase.

At the helm of this searingly intense production, BSC’s new artistic director Alan Paul bounds out of the gate with a brave new Cabaret, having made bold directorial choices in every aspect of the musical. The payoff is a spectacular, spellbinding, devastating show that will stick with viewers long after they leave the Kit Kat Klub. In addition, he surfaces the contemporary relevance without hammering it over your head. After this exceptional debut, I’m sure I’m not alone in anticipating what Paul will do for an encore.

Barrington Stage Company’s production of Cabaret at the Boyd-Quinson Stage in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, runs through July 8.

Be the first to comment