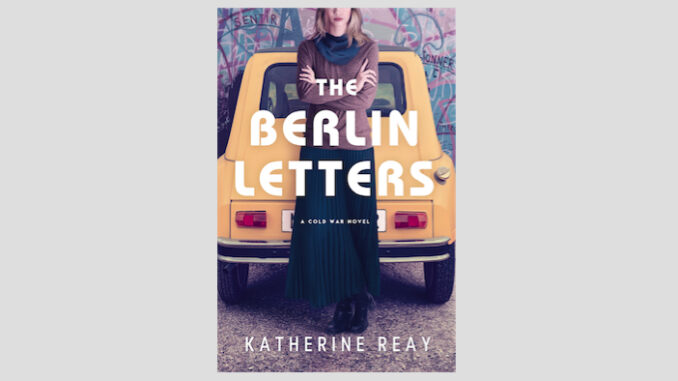

When I first came across The Berlin Letters by Katherine Reay (available now from Harper Muse), I was immediately intrigued. The page-turner, which takes place during the Cold War, is centered around a woman named Luisa Voekler who works for the United States government in DC in the late 1980s, and who stumbles upon some significant secrets within her own family after the death of her grandfather. This novel is one that is certain to grab readers from the first page and keep them engaged until the very end. Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with Katherine. Read on to see what she had to say about the story behind the story, importance of knowing our history and remembering the lessons it has to teach us, the power of literature and importance of understanding others’ perspectives, her own influences as a writer, some of her favorite reads, and much more.

Andrew DeCanniere: First, I wanted to say I think your book truly is an intriguing read. It’s also interesting how things seem to somehow have this way of coming back around. I feel as though many people thought we’d moved on from the Cold War years — a period you write about in your latest novel, The Berlin Letters. However, as we’ve seen recently, perhaps that isn’t quite so. It feels as though the world might not have progressed as much as we would like to think it has. One need not look further than what is going on in Ukraine. So, it does feel like a considerable step backward.

Katherine Reay: Yeah. Humans keep making the same mistakes. I agree with you. That’s one of the reasons I really like to focus on that period. If we forget the lessons of the past, if we are not vigilant, and if we don’t continue to talk about them — and be very real about what happened — then these things can and will happen again. It’s a little strange, and yet part of me says it is not unexpected, because we do forget, and then we find ourselves in these same cycles again. Hopefully we have learned, and hopefully we can redirect and shift course more quickly, with less pain and suffering. I don’t know.

DeCanniere: Getting to the story behind the story, how did you decide you wanted to write this book? When did you decide that this is something you wanted to pursue?

Reay: My previous novel takes place in Moscow from 1955 to 1985. There are two agents — one woman working for the CIA, the other working for MI-6 — who are kind of circling each other, and Moscow, and then have to escape in 1985. I was doing a lot of Cold War history research. Of course, you can’t do any such research without running into the most iconic symbol of the Cold War — the Berlin Wall. However, it wasn’t appropriate for that book. So, there was a little nod at it, but then when I was thinking about the book that became The Berlin Letters, it was inspired by both the Berlin Wall and really understanding what it did to a people.

It divided the city in a single day. If you were separated from your family on that particular day, you were separated from them for 28 years. The 65,000 people who lived in East Berlin, but who walked across to West Berlin every day for work, lost their jobs and livelihoods in a single day. That intrigued me not only in terms of the structure of the novel — as you know, the novel begins on the day the Berlin Wall goes up, and it ends on the day it comes down — but also how, as a character, the Wall affected peoples’ lives for 28 years.

When I stumbled upon the Venona Project — which was a real CIA codebreaking project — I figured out how one could get messages across the Wall, and the whole idea of the story came together. It was sort of piecemeal, but it felt so synergistic — as though the answer to the story was there all along — once I put those two pieces together.

DeCanniere: And just as you were sort of alluding to learning from the past, in keeping with the theme, I think you really cannot discuss the Cold War without also talking about World War II.

On the one hand, I have empathy for people who suddenly had the Wall running through their city — people who were abruptly and devastatingly cut off from their families, friends, and jobs. I cannot imagine something like that happening at any point, for any length of time. So, to have that happen and then for the Wall to stay up for 28 years? That is truly unfathomable.

On the other hand, I am also mindful that this basically happened in the aftermath of World War II — as, it could be argued, the direct result of the events of World War II. Therefore, I feel sorry for those who were on the right side of history — people who were against Fascism, who stood against the Nazis, and who refused to be a part of that machine — and then still ended up getting trapped in East Germany. As far as those who were on the wrong side of history are concerned, I cannot say that I feel anything for those who were on the side of the Nazis, and who were a part of the machine.

As far as the division of Germany into East and West itself is concerned, I think it is arguable that it occurred as the direct result of Germany’s own actions during World War II. If the Nazis had not been permitted to come to power, if the Holocaust had not happened, and if six million Jews — plus millions of others — had not been murdered, then Germany would not have been divided up the way that it was. There likely would not have been an East Germany and a West Germany. Unfortunately, the Nazis did come to power. The Holocaust did happen. Six million Jews and millions of others were murdered. And so East and West Germany were divided, as a direct result of the atrocities that Germany engaged in during World War II. That division was among the consequences of the Nazis’ heinous, barbaric and inexcusable actions.

Reay: Right. The dividing of Germany came out of the Yalta Agreement, when Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt got together and divided up Germany, so that another war could not start. You are absolutely right and this whole thing comes out of World War II and the atrocities that occurred. You cannot divide any war, from World War I — and probably even prior to that — from those that came after. The Cold War is an extension of World War II. World War II was an extension — with a brief break in the middle, in the inter-war years — of World War I. History is just a long line. It is not discrete events without implications for what comes next.

DeCanniere: When you are looking back at a particular period, events may not seem to be connected, but I think that the reality is very different. I think there is more interconnectedness than there may initially appear to be, and it is so important to put things in the proper historical context.

Reay: I agree. I think where we get in trouble is when we forget that interconnectedness. It is a rope made of many strings, and you cannot cut one string without the whole rope unraveling a little bit. There are so many connections across the globe — one human story with so many implications.

DeCanniere: Absolutely. I just think that whole thing of how all that played into the Cold War is such an interesting — and, quite honestly, important — piece to understand.

Reay: It is absolutely important. These events build on each other. If you forget what happens in World War II, you do so at your peril. You know what I mean? You can’t forget, because you see the extension of that playing out throughout the 20th century. Let us not go back there again. Let us remember these lessons. So, talking about the Cold War does not mean that we don’t talk about what led to the Cold War.

DeCanniere: I also think that this book — and these kinds of discussions — are more relevant and important than ever, particularly given there are those who seem to be flirting with other political ideologies. There seem to be those who view dictatorships and autocrats as some sort of positive thing or some kind of solution, which I find to be deeply disturbing to say the very least.

I’m not saying our system here in the United States is perfect. It is definitely not without its faults. I’m aware of what is going on today, and I am aware of our history, and there can be no denying that we have had major problems over the years. That said, I do not think that dictatorships or autocrats present a solution. We need to improve upon what we have, and the United States being run by an autocrat — the United States becoming a dictatorship — is not an improvement. The country needs to be more accepting, more inclusive, and work for more people — not fewer.

Reay: If you think about it, a republic and a democracy is an experiment that we need to protect. To be able to voice your opinion and to affect change? That is a very good and powerful thing. When you look at Nazi Germany, and when you look at the totalitarian Soviet Union, you are talking about two different ideologies. The end result, however, is the same in the sense that the individual does not have a say. They cannot legally express dissent, and it is important to be able to legally do so. That is what keeps our government in check — our ability to say “I disagree.”

Katherine Reay is a national bestselling and award-winning author who has enjoyed a lifelong affair with books. She publishes both fiction and nonfiction, holds a BA and MS from Northwestern University, and currently lives outside Chicago, Illinois with her husband. For more information, log onto her website. You can also find her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Be the first to comment